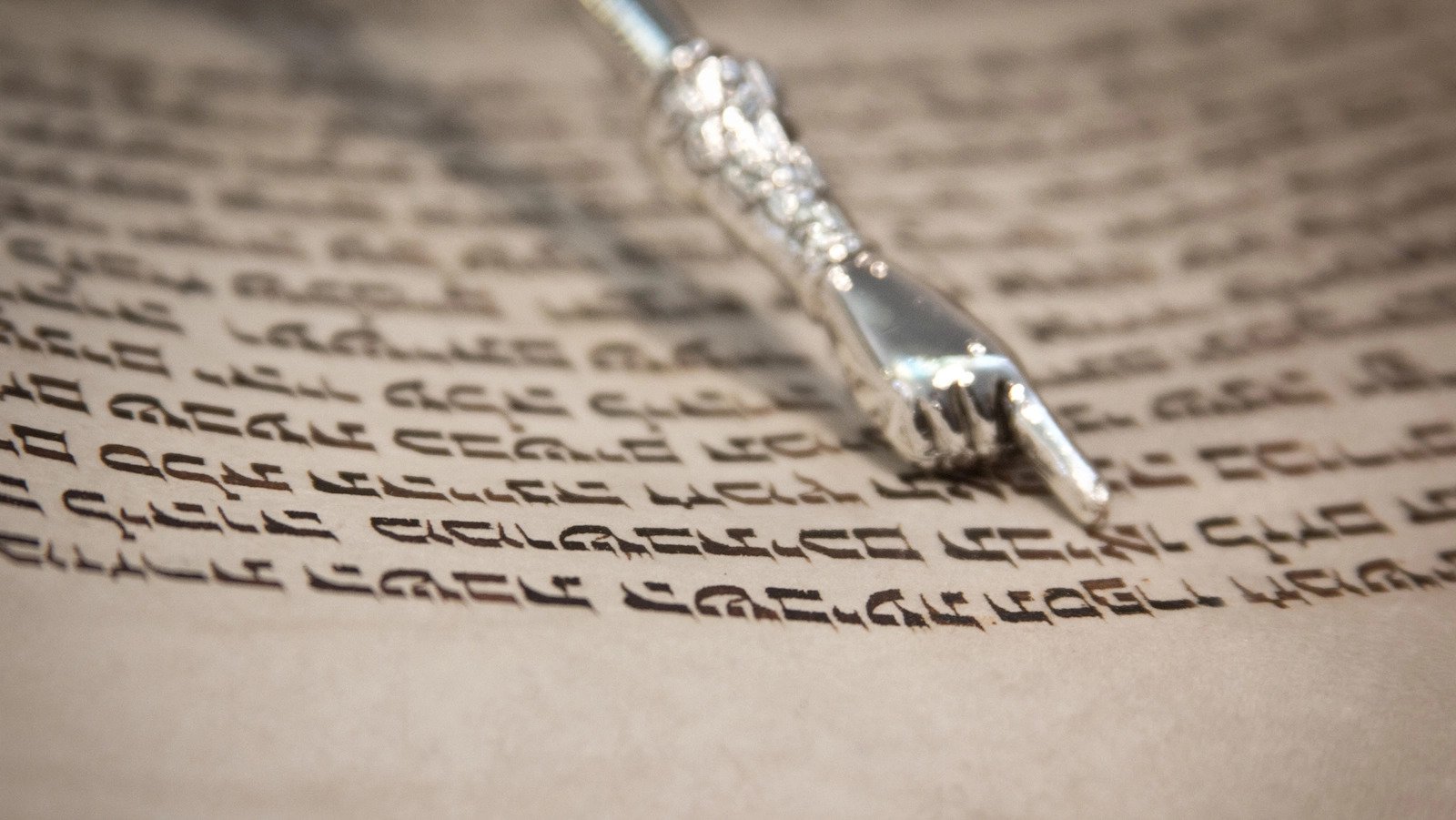

Interpreting the Torah

The Uniqueness of the Torah Tradition

During this lesson lessons, we are going to study the seven Noahide laws, how they are derived, and how they structure and shape the Divine vision for mankind. Since this exploration will be rooted in the ancient texts that make up Torah thought and theology, we should first introduce these texts and explain their purpose and how they work.

Although the seven Noahide laws have their origins in Adam and Noah, God chose to transmit and preserve them via Moses and the giving of the Torah at Sinai. This placed the Seven Mitzvos within the structure and system of Torah study and learning. Therefore, the seven Noahide laws must be interpreted and understood within the context of the Torah.

This point cannot be stressed enough: Jewish, and therefore Noahide, study and interpretation of the Torah is unique and unlike the study of any other religious texts.

In many non-Jewish (by implication, non-Noahide) religions, the Tanakh, the Torah, Prophets and Writings, are all treated with equal authority. Some even treat the later prophets with greater authority than the Torah itself.

This is not how Torah is viewed by those of Jewish, and by extension, Noahide faith. We view the Torah, Prophets, and Writings as hierarchical – there is an order of greater and lesser authority.

At the pinnacle of this hierarchy are the five books of the written Torah – the Chumash. They are the final, permanent, crystallization of God’s will for mankind. The Torah will never be replaced or superseded by any other future covenant or revelation.

In the textual realm, the Torah is the primary text for deriving law and practice for both Jews and Noahides.

The Five Books of Moses (the Chumash) is the most succinct possible written expression of Torah. However, the written Torah is only a gateway, an entry point into the larger world of Torah.

The Torah has many ambiguities but the Psalms refer to the Torah as perfect:

The Torah of God is perfect, restoring the soul… Psalms 19:8

There are a great many ambiguities in the Torah, so how then can a perfect text contain so many ambiguities? The answer is that Torah is not merely the text of the Torah. There is an orally transmitted, experiential component to the Torah, one which clarifies the ambiguities and, in combination with the written text, is called perfect. There are a number of sources for the need of the Oral Transmission: Albo, Sefer HaIkkarim III: 23. For other proofs to the necessity of an orally transmitted component of the Torah, see Kuzari 3:35; Moreh Nevuchim I:71; Rashbatz in Mogen Avos Chelek HaFilosofi II:3; Rashbash Duran in Milchemes Mitzvah, Hakdama I. See also Rashi to Eruvin 21b s.v. VeYoser; Gur Aryeh to Shemos 34:27.

The Jewish View of Tanakh (Scripture)

In many non-Jewish (by implication, non-Noahide) religions, the Tanakh,1 the Torah, Prophets and Writings, are all treated with equal authority. Some even treat the later prophets with greater authority than the Torah itself.

This is not how Torah is viewed by those of Jewish, and by extension, Noahide faith. We view the Torah, Prophets, and Writings as hierarchical – there is an order of greater and lesser authority.

At the pinnacle of this hierarchy are the five books of the written Torah – the Chumash2. They are the final, permanent, crystallization of God’s will for mankind. The Torah will never be replaced or superseded by any other future covenant or revelation.

In the textual realm, the Torah is the primary text for deriving law and practice for both Jews and Noahides.

The Prophets and Writings

If the Torah is the ultimate revelation of God’s will, then what is the need for later prophecy?

The main purpose of prophecy was to correct the people when they strayed from proper conduct or allegiance to the Torah. Therefore, the prophets and writings contain a treasure trove of moral inspiration and contemplation.

As for their practical interpretation, the prophets and writings do not come to, God forbid, alter or emend the Torah; The Torah is eternal and perfect. Rather, the Prophets and Writings play a supporting role. They are often used to clarify the meanings of certain proper nouns that occur in the Torah. They are also used as support, yet not proof, of Rabbinic laws, customs, and interpretations.

The Many Facets of Torah

The Five Books of Moses (the Chumash) is the most succinct possible written expression of Torah. However, the written Torah is only a gateway, an entry point into the larger world of Torah. The Torah is so vast, so all encompassing, that it is impossible to be entirely captured in writing.

Committing ideas to writing has many advantages – it creates permanence and a basis for interpretation. However, certain things cannot be expressed effectively in writing. For example, learning to sew, or paint from text alone is virtually impossible. One must be taught by someone with greater knowledge then himself. He must also be shown examples and have certain techniques demonstrated.

The situation is no different when trying to capture the infinite will of God in the finite language of man. A close reading of the Torah reveals many ambiguous, unclarified statements and terms. For example:

• And it shall be for a sign upon your hand, and as totafot between your eyes; for with a mighty hand did the LORD bring us forth out of Egypt. – Exodus 13:6

o The word totafot occurs in two similar passages (Deuteronomy 6:8 and 11:18), yet is not defined nor does it have any helpful Hebrew cognates.

• Similarly, The Torah writes: …When you shall say ‘I want to eat meat’… you shall slaughter of your herd and flock, according to how I have commanded you.” –

Deuteronomy 12:20-21

o The Torah is referring to some method of slaughter commanded by God; however the Torah nowhere records this method.

• This month shall be for you the first of the Months – Exodus 12:2.

o What month is being referred to? Egyptian months (where the Jews lived), or Chaldean months (where Avraham came from). Is the Torah talking about Lunar or Solar months?

• Let no man leave his place on the seventh day – Exodus 16:29.

o What “place” may man not leave on the Sabbath? His home? His City? His recliner?

• Jethro instructed Moses to appoint judges and to: enjoin upon them the laws and the teachings, and make known to them the way they are to go and the practices they are to follow. – Exodus 18:20.

o If the written Torah is complete and the only guiding force, then what is left for Moses to instruct? As well, the phrase: …make known to them the way they are to go…, informs us that there is some system or method by which judges are to rule.

Despite all of these ambiguities, the Psalms refer to the Torah as perfect:

The Torah of God is perfect, restoring the soul…3

How can a perfect text contain so many ambiguities? The answer is that Torah is not merely the text of the Torah. There is an orally transmitted, experiential component to the Torah, one which clarifies the ambiguities and, in combination with the written text, is called perfect.4

The Torah itself explicitly alludes to this larger conception of the Torah in Leviticus 26:46: These are the statutes and the ordinances, and the Toros [plural of Torah] that God has given…

If the written Torah was the only expression of Torah, then the verse would simply read: This is the Torah that God has given! However, the verse refers to much more: the multiple facets of the Torah.

The Oral Law Exists for a Number of Reasons

It explains concepts that cannot be fully captured in writing,

It defines unusual or rare terminology,

Most importantly, it provides a system of interpretation. This system of interpretation is crucial because it gives us three things:

a. It guides us in the application of the Torah to new situations and new scenarios,

b. It gives us standards and guidelines by which we can evaluate the legitimacy of interpretations and applications of the Torah, and

c. It provides a means by which we can reconstruct any details of correct observance should it become blurred or forgotten due to exile and oppression.

Mesorah - Transmission

The most important element in validating interpretations of the written and oral Torah is the concept of Mesorah. Mesorah is, without question, the greatest proof to the authenticity of any concept, practice, or interpretation.

The closest translation Mesora is probably “transmission,” the giving over of information. It refers to an unbroken chain of transmission from the revelation at Sinai until the present time. Authenticity of concepts and practices is strongly based upon Mesorah.

Even archaeological evidence does not carry the authority of the Mesorah. Archaeology is concerned with reconstructing forgotten things based upon a minute amount of evidence. Mesorah is known information transmitted from generation to generation without having been forgotten. When a known break occurs in the Mesorah, the chain of transmission, and it has a practical effect on observance, we do not attempt to resurrect the Mesorah based on archaeological evidence. For example, knowing which cities in Israel were walled in ancient times is important for a number of laws. The Mesorah, transmitted knowledge, is what we rely on to determine which cities were walled. Archaeological evidence is insufficient proof.

Writing Down the Oral Law

For much of Jewish History, the oral Torah was not written down. It was part and parcel of the culture of a unified people living in a single location. Its integrity was also maintained by a central authority, the Sanhedrin. However, as the threat of exile loomed large and the Sanhedrin’s authority waned under Roman persecution, the Rabbis realized that the transmission of Torah study and Mesorah was in danger.5

They began to write down as much of the material as possible. Their vision for this redaction was two-fold:

To create a representative literature of the oral component of Torah in a form that was compact and efficient for study and memorization, and

Create a statement of the oral law that, by way of study, would teach and preserve the correct method of Torah study and interpretation.

The final product of this effort was the Mishnah.

1 The complete Hebrew Bible is referred to as the Tanakh. The word is an acronym for Torah (Five Books of Moses), Neviim (Prophets), and Kesuvim (Writings).

2 The word Chumash is the common term for the Five Books of Moses. It is a Hebrew word that means “fifths” – a reference to the five books.

3 Psalms 19:8.

4 Albo, Sefer HaIkkarim III: 23. For other proofs to the necessity of an orally transmitted component of the Torah, see Kuzari 3:35; Moreh Nevuchim I:71; Rashbatz in Mogen Avos Chelek HaFilosofi II:3; Rashbash Duran in Milchemes Mitzvah, Hakdama I. See also Rashi to Eruvin 21b s.v. VeYoser; Gur Aryeh to Shemos 34:27.

5 See Temura 14b.